Rojava: statelessness in a time of pandemic

Lack of international recognition as a state has disastrous consequences on an area already suffering from war and displacement.

The Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES), commonly known as Rojava, has illuminated the plight of the stateless—even though statelessness in the AANES’s case defies the narrow definition of international law. Despite comprising almost a third of Syrian territory, the AANES has not been recognized as a legitimate body politic neither by the Syrian state, nor by the international community. The limitations that come with this lack of recognition may have disastrous consequences during the COVID-19 pandemic.

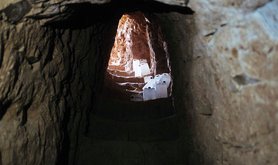

War-torn, under attack, and facing a pandemic

The AANES faces dire humanitarian conditions caused by years of war against ISIS and further aggravated by the recent Turkish invasion in October 2019. Six-hundred thousand IDPs and refugees, largely a product of two occupations by Turkey, live in camps across the region, where access to water is limited and social distancing is all-but-impossible. In addition, there are tens of thousands of ISIS prisoners and their families guarded in camps and prisons by the local administration. Since their countries of origin have been unwilling to repatriate them or to put them on trial, this burden has fallen on the AANES. Overall, the administration has few resources to ensure adequate protection and healthcare for its vulnerable populations—especially in the context of a pandemic.

Join the COVID-19 DemocracyWatch email list

Sign up for our global round-up of attacks on democracy during the coronavirus pandemic.

We’ve got a newsletter for everyone

Whatever you’re interested in, there’s a free openDemocracy newsletter for you.

The region’s health care system has been heavily affected by war, with only 2 of 11 hospitals fully operational. There are only 40 ventilators to serve a population of up to 5 million, and given an acute lack of beds and medical practitioners, the region has the capacity to treat less than 500 cases. Moreover, Turkey, which occupies parts of the region, has been regularly cutting the water flow to the AANES, leaving up to a million people without clean water. To make things even worse, attacks by Turkish forces and Turkey-backed militias continue despite the UN’s call for a global ceasefire due to the pandemic, which was observed by the Syrian Democratic forces (SDF).

Given these conditions, one would expect international institutions to help prevent the spread of COVID-19 in the region. Instead, the UN and the WHO have refused to provide direct support to the AANES because of their policy of working only with or through a country’s official representation, even though that means leaving the Autonomous Administration at the mercy of the hostile Assad regime.

No state, no aid

Access to humanitarian aid was a challenge for the Autonomous Administration even before the pandemic, largely due to the lack of international recognition and support. Following Turkey’s invasion last year, the region saw the departure of the biggest international aid organizations. Besides facing the threat of attacks by Turkish-backed forces, they had to leave as they were not registered with the Syrian government: since the Syrian forces entered the region as part of the agreement with the SDF to stop the Turkish offensive, registration with Damascus became a requirement.

In addition, in a move to increase the AANES’s reliance on Damascus, Russia used its leverage at the UN Security Council earlier this year to close the only UN aid crossing into the AANES from Iraqi Kurdistan, through which 40% of the region’s medical supplies used to be delivered. Now, UN aid sent to Syria goes directly to Damascus even though the regime is known for misusing funds and blocking humanitarian support to the AANES.

The situation has now been exacerbated by the pandemic, highlighting the exclusion of non-state entities from the international humanitarian system. Because the Autonomous Administration is not a government, it cannot negotiate a bulk deal for protective gear like gloves and face masks; instead, it must purchase them on the open market at full price. The lack of WHO and UN presence in the region also means that NGOs on the ground are not able to access the $2 billion UN fund dedicated to the COVID-19 response. Following the outbreak of the pandemic, the UN instructed its relief agencies to only fund private charities in the northeast that are registered with Damascus because of the earlier closure of the UN aid crossing.

Yielding to the pressure of the Assad regime, which appears to be deliberately sabotaging the AANES’s efforts to address the pandemic, the WHO has been providing all COVID-19 aid to the Syrian government. It refused to supply test kits to the AANES, maintaining that the latter is not a state and therefore cannot be dealt with directly. Instead, the WHO demanded that the region send all samples to Damascus for testing, despite the Administration’s warnings about the unreliability of this approach. The Administration’s misgivings were proven true as the WHO failed to report the first COVID-19 case in North and East Syria. Informed by the Syrian government about a positive test result, it kept quiet for 11 days until an NGO operating in the region communicated the news to the AANES. This is only the most egregious example of various bureaucratic hurdles created by Damascus, which the UN and its agencies have failed to challenge.

In contrast, the WHO provided test kits to the opposition-held province of Idlib through Turkey, who backs the jihadist groups controlling the northwest of Syria. UN agencies and other organizations also continue delivering aid to the region through the Turkey border which has remained open in contrast to the border crossing to the AANES. While Turkey has secured some support for its proxies in northwestern Syria, there has been no push by any member of the multinational anti-ISIS coalition for concerted measures to help the AANES deal with the pandemic—thus leaving it at the mercy of the hostile Assad regime.

AANES responds to the pandemic

Despite these challenges, the Autonomous Administration demonstrated its ability to provide for its population even under dire circumstances. Early on during the pandemic, the administration took measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19 by closing border crossings and announcing a region-wide lockdown. The first specialized, 120-bed hospital for coronavirus cases has been recently set up, although it can only handle medium-severity cases, and more facilities are planned across the region. At the same time, the Administration has tried to mitigate the economic consequences of the lockdown by waiving utility bills, lowering food prices and coordinating home deliveries of essential goods through local structures. With schools and universities shut down, online lessons and lectures have been launched to meet educational needs under the curfew.

Local structures at work

As mutual aid initiatives spring up across many wealthy countries struggling to provide basic goods and services, the AANES may offer an instructive example to those who are looking for viable alternatives to “going back to normal.”

As Meghan Bodette convincingly argues, the AANES’s bottom-up political and economic structures, built according to the principle of decentralized governance, have played an important role in the region’s response to the crisis. Many cooperatives, the pillar of the new economic vision, and local production workshops, have swiftly adapted to meet the demands of the pandemic. As a result, they started producing masks to be distributed to pharmacies, members of local security forces, and—through neighborhood communes, the smallest unit of the new bottom up political system—to the general population. Communes, which are in direct contact with neighborhood residents, have been responsible for registering people in need of aid and distributing basic goods to them on a house-to-house basis. At the same time, the relationship between cooperatives, communes and other institutions of the AANES has enabled an effective coordination of efforts.

Bottom-up political and economic structures, built according to the principle of decentralized governance, have played an important role in the region’s response to the crisis

There is no denial that the AANES has a very limited production capacity and has to rely on international support for things like medical technology. While there are attempts to produce ventilators to supplement the meager amount currently available in the region, success is yet to be seen. Nevertheless, the region’s bottom-up structures demonstrate an efficiency that has been disastrously lacking in many developed states.

“Nothing about us without us”

The pandemic has exposed the severe consequences of not having a state. The international nation-state system has proven utterly inefficient in providing for those whose status falls short of the only accepted political form, even when that means abandoning entire societies to the mercy of pandemics or dictatorial regimes. Instead of fulfilling its impartial humanitarian role, the UN and its agencies have catered to regional and global powers who get to decide which populations are allowed self-determination—and with it, access to the rights and benefits that come with an internationally recognized status. As Salih Muslim, a prominent politician in the AANES, described the situation, the UN chooses to work with governments and not with peoples.

While the US-led anti-ISIS coalition has delivered some aid to the AANES, this is woefully insufficient. The international community should pressure the UN to work directly with the AANES to help it weather the pandemic. And those of us in the West who want to see this model of feminist, pluralist and ecological democracy thrive have to pressure our governments to end their complicity with Turkey’s long-standing war on Kurds, recognize the AANES’s autonomy under international law and ensure its representation in the UN-sponsored Syria peace talks in order to end its plight of statelessness.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.