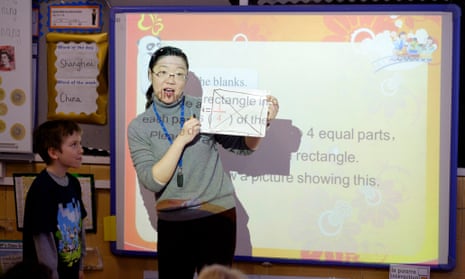

Lilianjie Lu stands in front of 21 seven and eight-year-olds in a London classroom, struggling slightly with her English but with a winning smile on her face, as she attempts to teach them all about fractions.

Lu has left her five-year-old daughter, her husband and her job as a primary school teacher in Shanghai to come to England to teach children maths – the Chinese way.

The classroom has been reconfigured to resemble a Shanghai classroom. The carpet has been taken up, desks which are normally clustered in friendly groups are in straight rows, and all eyes are on Lu and her touchscreen.

She is one of 30 Shanghai teachers currently working in primary schools across England, flown in by the Department for Education in the hope they can work their mathematical magic on a generation of children and raise flagging standards.

Shanghai is one of the the top-performing jurisdictions in the Pisa global education league tables, which suggest that by the age of 15, children in Shanghai are up to three years ahead of their English peers in maths.

Almost all Shanghai pupils reach a similarly high standard and there are few gaps in achievement (unlike in England where there is a wide range in attainment). Lu and her colleagues are here to show us how they achieve their extraordinary results.

The government has invested £11m in a two-year programme to boost England’s performance in maths, but many in the education world remain sceptical about attempts to copy the Shanghai model.

Fractions are apparently particularly challenging for English children, so Lu is devoting her three-week stay at Fox primary school in Kensington to halves, thirds, numerators and denominators.

It may be worth noting that the children at Fox are already pretty good at maths. Fox is one of the best performing primary schools in the country, but 25 other schools currently have their own Miss Lu, 22 schools were part of a similar programme last November, and the aim is that good practice will be shared with other schools.

To that end, at the rear of the classroom sits a small group of observers – teachers from nearby schools – who watch and take notes. Next year the Shanghai exchange expands to secondary schools.

Lu begins by asking the children to read out the fractions on the screen. One child gives the answer – “a half” – then the rest of the children repeat. Another child identifies a third, everyone repeats, a quarter, and so on.

At the end of this part of the lesson the children give themselves a clap – not a boisterous round of applause with whoops and cheers, but five precise claps in a set rhythm. Then the children read the fractions out all over again before Lu moves on to how to write fractions.

There is nothing random about how to write a fraction, it turns out. First you draw the line, then you write the denominator (below the line), and finally the numerator, above the line. In that order.

“Can you write the fractions now? Yes or no?” she asks the children. The children write them in their books then are called out individually to the front to write them on the board. Five more tidy claps.

The class is repetitive, going over and over similar territory, stretching the children slightly further as the lesson progresses, picking up on mistakes and making sure that everyone is keeping up.

This is the “Shanghai mastery approach”, a methodical curriculum, aimed at developing and embedding a fluency, deep knowledge and understanding of underlying mathematical concepts.

“English teachers would have moved on so much more quickly,” whispers Ben McMullen, deputy head at Fox school and senior lead in the local maths hub. “They dwell on it for what seems a long time so every single child understands exactly what’s going on. We move them on too quickly before they’ve properly understood the principle.”

Lu is now asking the children what a fraction is. “If the whole is divided in to three equal parts, each part is a third of the whole,” one child explains. The other children follow suit, repeating and adapting their answer to explain the fraction written on the board.

“There’s a lot of chanting and recitation which to our English ears seems a bit formulaic,” says McMullen, “but it’s a way of embedding that understanding.”

Last September McMullen was one of 71 English teachers to travel to Shanghai where they spent two weeks in local primary schools and he is still brimming with enthusiasm at the quality of the maths teaching he saw there.

To start with the lessons are much shorter – 35 minutes in Shanghai followed by 15 minutes unstructured play, half what McMullen usually delivers at Fox. “I saw better maths teaching in 35 minutes than I had ever done in an hour and ten minutes,” he says.

In Shanghai every child of the same age is on the same page of the same text book at the same time. Setting and streaming do not exist - there’s an expectation that every child will succeed.

Children have mastered their jiujiu (times tables) back to front and inside out by the time they are eight. Classrooms are bare and text books are basic, minimal, “not that appealing” to look at, admits McMullen, but of exceptionally high quality and thoroughly researched.

The classroom where we are sitting, in contrast, is filled with colourful, interesting work stuck all over the walls; one display shows the word of the day is “Shanghai”, the word of the week is “China”, an untidy row of violins lean up against the wall and children come and go to music lessons. Perhaps our children are suffering from sensory overload, ponders McMullen.

When Lu is working at her usual school, Shanghai Zhaibei District Experimental Primary, she teaches just two lessons a day; she only teaches maths, the rest of the day is spent debriefing and discussing maths. An English primary teacher, in contrast, is a generalist, teaching all subjects, all of the time.

Likewise, the teacher training models for China and England could hardly be more different. Lu spent five years at university studying primary maths teaching; trainee teachers on programmes like School Direct will spend less than two weeks concentrating on maths.

Ruth Merttens, professor of primary education at the University of St Mark and St John, is one of those who is sceptical about importing Shanghai teaching techniques to England.

She questions how compatible Shanghai methods are with the diversity of children in English schools, which cater for children of many different nationalities and backgrounds, as opposed to the more homogeneous intake in Shanghai.

“I’m sure we can learn from the Shanghai teachers, some things will be appropriate, others will not. But one thing I would say is that there’s very little money in education at the moment. If I were spending money, that would not be where I would choose to spend it.

“In England we have a very diverse set of communities. Sitting in rows conforming to a one-size-fits-all education, that’s not 21st century Britain.

“In England we expect children to enjoy primary education, to feel they are in some sense in the driving seat for their own learning, or at least have a hand on the steering wheel.

“In Shanghai it’s about delivery – it’s a different model. Culturally we are millions of miles apart.

“We’re not better, we’re different.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion