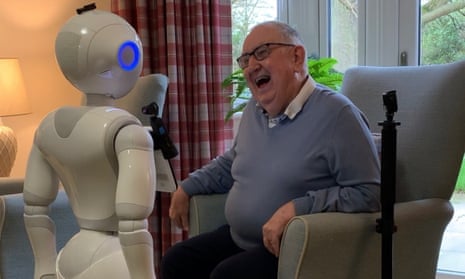

Robots that can hold simple conversations and learn people’s interests are to be deployed in some UK care homes after an international trial found they boosted mental health and reduced loneliness.

The wheeled robots, called “Pepper”, move independently and gesture with robotic arms and hands and are designed to be “culturally competent”, which means that after some initial programming they learn about the interests and backgrounds of care home residents. This allows them to initiate rudimentary conversations, play residents’ favourite music, teach them languages, and offer practical help including medicine reminders.

The researchers, led by Dr Chris Papadopoulos at the University of Bedfordshire, said the trial was not intended to explore the replacement of human carers with robots, but to help fill lonely periods when, because of a stretched social care system, staff do not have time to keep residents company.

The trial, in the UK and Japan, found that older adults in care homes who interacted with the robots for up to 18 hours across two weeks had a significant improvement in their mental health. There was a small but positive impact on loneliness severity among users and the system did not increase feelings of loneliness, academics found.

The robots’ limitations centred on their conversations feeling superficial and lacking “richness”, users said. They lacked personalisation and sometimes did not show enough cultural awareness, and their head movements and hand gestures were sometimes distracting. The analysis was part of a £2.3m research project funded by the European commission and Japanese government.

Advinia Healthcare, a trial location and one of the largest providers of dementia care in the UK, said it was “working towards implementing this into routine care of vulnerable people to reduce anxiety and loneliness and provide continuity of care”.

“This is the only artificial intelligence that can enable an open-ended communication with a robot and a vulnerable resident,” said Dr Sanjeev Kanoria, the Advinia chairman. “Now we are working towards bringing the robot into routine care, so it can be of real help to older adults and their families.”

He said the robots would not directly lead to job cuts but would be worth using because happier residents mean less work for staff and improve satisfaction ratings, boosting occupancy.

The initiative comes amid a continuing staffing crisis for UK care homes exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic, during which more than 18,000 residents have died of confirmed or suspected Covid-19.

Before the outbreak, the care industry had at least 120,000 vacancies and the largest operators this week told MPs that staff are suffering “burnout”, and the strain is being increased by the financial difficulties many operators are facing, after costs soared and occupancy levels fell.

A single robot loaded with software costs about £19,000, about £1,000 more than the average salary of a care worker in south-east England. But cheaper robots could also be used.

Care England, which represents the largest providers, said the robots were not likely to replace staff but might help create deeper and higher-quality relationships with residents.

“In the UK alone, 15,000 people are over 100 years of age and this figure will only increase,” said Irena Papadopoulos, a professor of transcultural health and nursing at the University of Middlesex. “Socially assistive, intelligent robots for older people could relieve some pressures in hospitals and care homes. No one is talking about replacing humans – the evaluation demonstrates that we are a long way from doing that – but it also reveals that robots could support existing care systems. While results demonstrate that our experimental robot was more culturally competent to users, they also reveal that there is room for improvement.”

Vic Rayner, the executive director of the National Care Forum, which represents charitable care providers, said: “Robots in social care should not be seen as part of a frightening futuristic vision. They offer key additions to how care is delivered that need to be explored further and understood. Covid-19 has shown us that rather than being a sector which does not understand technology, it is in fact one that is ripe to explore how technology can improve efficiency, support data flow and enhance communication with families and loved ones.”