Instagram and other Social Media Apps. Jason Howie / Flickr. Some rights reserved.

The role of online

platforms in elections has been much discussed in the aftermath of the US

presidential election, with fake news and targeted advertising on social media

hotly debated. Our pre-election review assesses available data on key online

trends in this year’s UK General Election. We begin by an overview of the

growing importance of social media for political news and opinion, followed by

a large-scale analysis of political content distribution on Facebook during the

campaign period. Finally, we examine current practices in political advertising

online.

The content discovery mechanisms on Facebook in particular are shaking up the

UK’s partisan press landscape. Highly opinionated, pro-Labour online

publications with no direct print equivalents (such as The Canary and Evolve

Politics) are reaching larger Facebook audiences for their content than most

national news brands, and overall coverage weighted by distribution is much

more left-leaning on social media than in print or on major news websites on average.

The shift is at least in part due to the youth of the Facebook user base

relative to likely voters, and it remains to be seen whether Labour’s warm

reception on social media will translate into a higher youth turnout. However

it is already clear that Facebook as a political news platform favours stark

opinion over reporting — even more than print newspaper layouts and news

websites.

Facebook is also taking the lion’s share

of both the main parties’ online campaign ad budgets, with Labour determined

not to be outgunned on the platform as it was in 2015. The platform’s ad

targeting tools are much better at digesting voter databases than they were

during the last General Election, making it a powerful tool for targeted

campaign messaging in marginal constituencies. Little data on the targeting and

reach of the parties’ Facebook campaigns will be available until after the

election, but the use of voter data has already prompted an investigation by

the Information Commissioner's Office and citizen group Who Targets Me?.

Social media tilts online news against May and the conservatives

Facebook is the most important social media channel, but users still skew younger than voters

The coverage of the two main parties in the national press, weighted by circulation, has consistently been much more negative to Labour than towards the Conservatives during the campaign[1], but the evidence we have suggests that political news discovery on social media is tilting the online news coverage in the opposite direction.

To analyse political content distribution on social media, we took a sample of 22,000 pages of online content shared between 19th April and 5th June using BuzzSumo, a social media research tool which makes use of the public data interfaces of Facebook, Twitter and other social media platforms. Due to the presidential nature of this election campaign, we focused our analysis on news coverage of the two main party leaders.

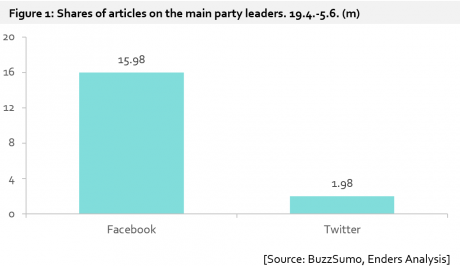

Facebook was by far the most important social media channel for political news distribution during the campaign period, with 16m content shares of articles or videos on either Theresa May or Jeremy Corbyn over the six-week tracking period (see Figure 1 for a comparison with overall shares on Twitter).

Although not perfectly indicative of overall post views on Facebook and referral traffic to publisher sites, shares are the best publicly available proxy metric for audience reach on the platform. Because Facebook’s news feed algorithm favours engagement and perceived personal relevance, each share both exposes a post to more personal news feeds as well as improves its ranking on them. Estimates of how many post views each share on average corresponds to range from 2 to 20 or more. As for referral traffic to publisher websites, Facebook’s growing importance is clear: according to comScore data the platform now accounts for around a quarter of all inbound traffic to national newspaper websites, up from 5 per cent in 2013. For online native publishers, the share is typically higher (often well over half of all traffic).

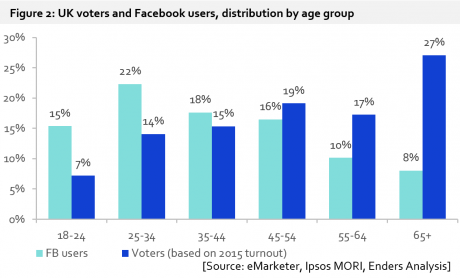

However, the Facebook audience skill skews young, certainly relative to the demographics of voters in recent General Elections. According to our estimates, 56.4% of UK population of voting age are Facebook users, but when adjusted for 2015 turnout by demographic the number is slightly lower at 52.7% (assuming no correlation between FB usage and likelihood to vote apart from age distribution). This is only slightly up from the 2015 General election.

Scathing coverage of Theresa May, but little fake news in sight

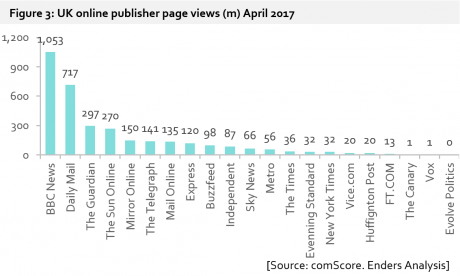

According to data from comScore, overall traffic to UK news websites is still dominated by established news brands with strong print newspaper circulations or a presence on TV (see Figure 3).

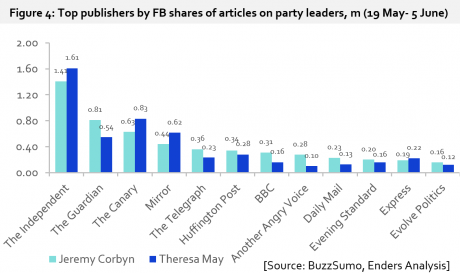

But for the election coverage widely shared on Facebook, the picture is vastly different. Online native news sites like The Canary and even blogs like Another Angry Voice were able to achieve larger audiences than many strong print and TV news brands (see Figure 4). Notably, the Express which was the most successful publisher on Facebook for Brexit-related content did not perform particularly well.

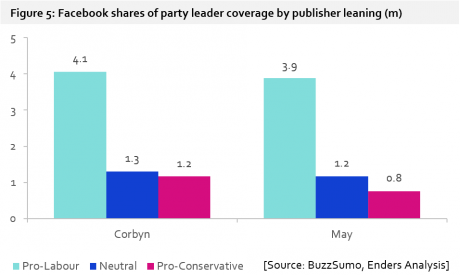

The high rate of sharing for the Independent, Guardian, Mirror and online native pro-Labour publishers such as The Canary and Evolve Politics contributed to a highly pro-Labour skew in Facebook shares. While the number of articles shared was quite evenly spread between pro-Labour and pro-Conservative, the total number of total shares tilted heavily towards content against May and for Jeremy Corbyn (see Figure 5). On Twitter, the news and opinion shared was similarly highly supportive of Corbyn on average. Worryingly for the UK’s biggest news brands, a common angle among much of the most shared content was criticism of the campaign coverage of UK national newspapers and public service broadcasters.

Facebook strives to give users what they want in terms of content by taking into account previous engagement with content on and off Facebook as well as social cues from close friends. The aggregate effect of this personalisation seemed to favour Labour, but it impossible to tell how much of the content sharing was among small groups of activists or those already very likely to vote Labour. Nevertheless, among these groups Facebook is conducive to getting across Labour’s party line efficiently and quickly, certainly more so than through the national press, strongly pro-Conservative in this election.

The most successful content was highly opinionated with strong political bent, but outright fake news sites were unable to gain large distribution on Facebook (just as they failed to do so during the Brexit referendum campaign, according to our analysis of news distribution during that period). Similarly on Twitter, a study by the Oxford Internet Institute found much lower levels of linking to “junk news” stories than in the US election, at 11.4% of the links shared vs 33.8% in the US sample. The share of election tweets thought to be by bots due to high frequency of tweets from the users in question was similar for both pro-Labour and pro-Conservatives tweets.[2

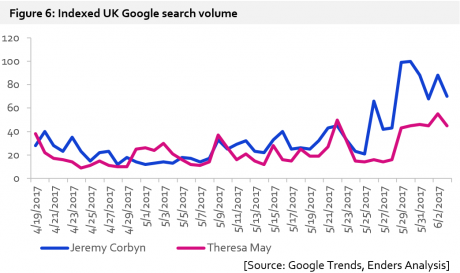

A late surge for Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour registered on Google

While news on Facebook was consistently favourable to Jeremy Corbyn throughout the campaign period, the pattern of search trends was more similar to the prominence of the two party leaders in the national press and on TV. Just as the press gave more (and more favourable) coverage to Jeremy Corbyn after the publication of the party manifestos[3], the Labour Party leader overtook Theresa May in search interest during the same period.

The increasing personalisation of Google search is likely a limiting factor to Google’s impact on voting intentions, with the surfaced news results predisposed to reinforce existing party leanings rather than challenge them (as they reflect past browsing and search histories as well as the location of the user).

Facebook dominates political advertising online

Growing budgets

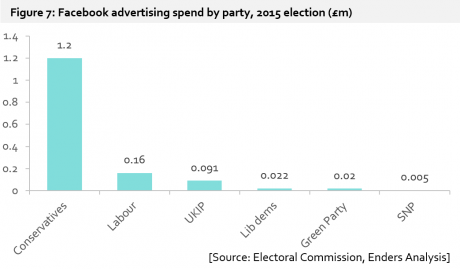

In the 2015 general election, the Conservatives pioneered a Facebook-heavy online advertising strategy, spending over £1.2m on the platform, almost 10 times the amount spent by Labour (see Figure 7) and three times the amount spent on YouTube ads by either party. This year, Labour pledged to spend £1m on Facebook ads, which cements Facebook’s position as the main digital advertising platform for the election. In terms of scale, a budget of this size in the UK is enough to serve well over a hundred million News Feed ad impressions on the platform, even with a high degree of audience targeting.

Data and targeting

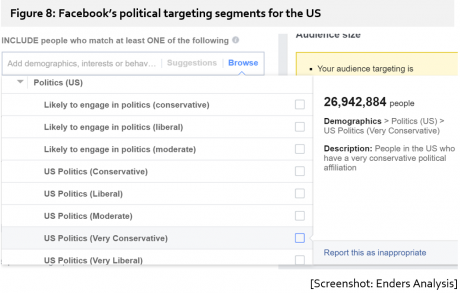

Facebook’s own political targeting segments (see Figure 8) are not available in the UK, but any campaign can upload its own audience data as a basis for ad targeting.

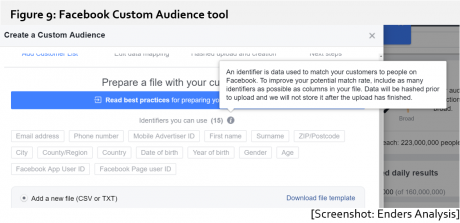

The parties are able to use both their own data (collected through volunteers and campaign websites), commercial third party datasets (we observed Conservative ads partly targeted with segments from data broker Axciom), or a combination of the two. The resulting datasets with associated personal identifiers such as name, age, gender, postcode, email address, date of birth or mobile advertising ID can then be segmented and uploaded to Facebook to create a Custom Audience for ad targeting (see Figure 9). Since the 2015 election, the list of identifiers supported by Facebook has grown longer. The more identifiers, the better the likelihood of a match, and Facebook’s audience targeting system is industry-leading both in accuracy and scale (see our report People, not devices Audience buying in a cross-device world [2017-035]).

In general, the campaigns’ privacy policies and disclosures on the use of data suffer from a lack of clarity. In the future, this may well result in regulatory action. Already, the Information Commissioner’s Office has launched an investigation “into the use of data analytics for political purposes”[4].

With aggressive Conservatives and defensive Labour, negative messages from both

According to data from Who Targets Me?, a group which uses browser plugins installed by volunteers to monitor campaign ads on Facebook, the Conservative campaign’s ads are targeted to marginal seats the party is hoping to gain from Labour, with strong emphasis on negative messages aimed at Jeremy Corbyn.[5]

The other side’s ads were also negative: out of 2,314 Labour Party messages captured by Who Targets Me?, 60% criticised other parties. But the campaign’s ad targeting was more defensive than that of the Conservatives, with a heavy focus on seats won by Labour in 2015.[6]

As long as the ads have a national message, Facebook ads do not count towards local campaign spending limits even if locally targeted.

Countering talking points with Google search ads visible to journalists but less important

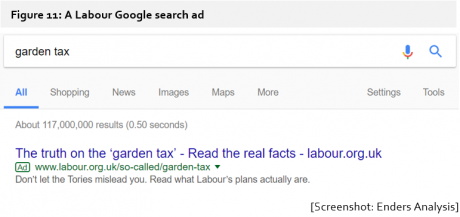

Press reports seized on the parties’ efforts to put out their own spin on negative characterisations by the other side on issues like the Social Care proposals in the Conservative manifesto (dubbed “Dementia Tax” by Labour) using Google ads. In practice, this was achieved by bidding on the harmful phrase put out by the opposing campaign (see Figure 11). While these ads were easier to observe than those on Facebook, their impact was considerably lower: according to data from search engine optimisation tool SEMRush, the search volume for phrases like Dementia Tax was very low.

This research note has been reproduced with persmission from Enders Analysis. For alerts, research and subscriptions please visit the Enders Analaysis publications page.

© 2017 Enders Analysis Limited. All rights reserved. No part of this note may be reproduced or distributed in any manner including, but not limited to, via the internet, without the prior permission of Enders Analysis Limited. If you have not received this note directly from Enders Analysis Limited, your receipt is unauthorised. Please return this note to Enders Analysis Limited immediately

[1] http://blog.lboro.ac.uk/crcc/general-election/media-coverage-2017-general-election-campaign-report-2/

[2] http://comprop.oii.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/89/2017/06/Social-Media-and-News-Sources-during-the-2017-UK-General-Election.pdf

[3] http://blog.lboro.ac.uk/crcc/general-election/media-coverage-2017-general-election-campaign-report-2/

[4] https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/may/17/inquiry-launched-into-how-uk-parties-target-voters-through-social-media

[5] https://www.buzzfeed.com/jimwaterson/conservative-election-adverts?utm_term=.thJYXXQjN#.kdjnggOEb

[6] http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/mediapolicyproject/2017/06/06/labours-advertising-campaign-on-facebook-or-dont-mention-the-war/

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.