Der, die or das? For centuries, the seemingly arbitrary allocation of masculine, feminine and neutral gender articles in German has driven non-native speakers to despair. "In German, a young lady has no sex, while a turnip has," the American writer Mark Twain once complained. "Think what overwrought reverence that shows for the turnip, and what callous disrespect for the girl."

But hope may finally be in sight. Changing attitudes to gender are increasingly transforming the German language, and some theorists argue that scrapping the gendered articles altogether may be the most logical outcome.

Predictions vary: one suggestion is that Angela Merkel will eventually no longer be die Bundeskanzlerin but a neutral das Bundeskanzler, as she would be in English. Others believe that the feminine gender, already the most common fallback form used by non-native speakers, will become the default article: a policeman would no longer be der Polizist but die Polizist.

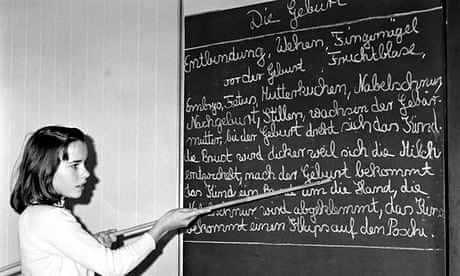

The changing nature of German is particularly noticeable at university campuses. Addressing groups of students in German has been problematic ever since universities stopped being bastions of male privilege. Should they be sehr geehrte Studenten or sehr geehrte Studentinnen?

In official documents, such as job advertisements, administrators used to get around the problem with typographical hybrid forms such as Student(inn)en or StudentInnen – an unfair compromise, some say, which still treats the archetype of any profession as masculine.

Now, with the federal justice ministry emphasising that all state bodies should stick to "gender-neutral" formulations in their paperwork, things are changing again. Increasingly, job ads use the feminine form as the root of a noun, so that even a male professor may be referred to as der Professorin. Lecturers are advised to address their students not as Studenten but Studierende ("those that study"), thus sidestepping the gender question altogether.

In the long run, such solutions would prove too complicated, linguists such as Luise Pusch argue. She told the Guardian that men would eventually get so frustrated with the current compromises that they would clock on to the fundamental problem, and the German language would gradually simplify its gender articles, just as English has managed to do since the Middle Ages.

"Language should be comfortable and fair," said Pusch. "At the moment, German is a very comfortable language, but a very unfair one."

Many linguists question whether language can be changed through human will. "It's hard to transform grammar through legislation, and even if so, such changes often happen over centuries," said Anatol Stefanowitsch, a linguist at Berlin's Free University.

But he also points out that some dialects, such as Niederdeutsch (Low German), have lost the cumbersome distinction between der and die already: in Low German, for example, both men and women are simply referred to as de.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion